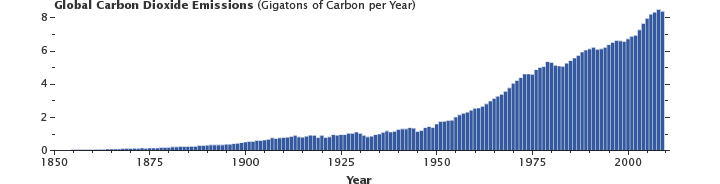

Climate change is arguably the largest global issue that we all face and the rate of global warming has increased dramatically in the past 100 years mainly due to increased human activity resulting in rising levels of greenhouse gases in our atmosphere. For this article, I will not go into too much depth about this, but the crux of the argument is quite simple: Increasing amounts of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases in our planet’s atmosphere add to the enhanced greenhouse effect whereby more solar radiation is trapped in our atmosphere resulting in increasing global temperatures.

Future effects of climate change remain uncertain but what is definite is that we are already seeing the effects of the phenomenon now. Speaking in Alaska in 2015 before the Paris climate deal was struck, the then President of the United States, Barack Obama, stated that ‘Climate change is no longer some far-off problem; it is happening here, it is happening now.’

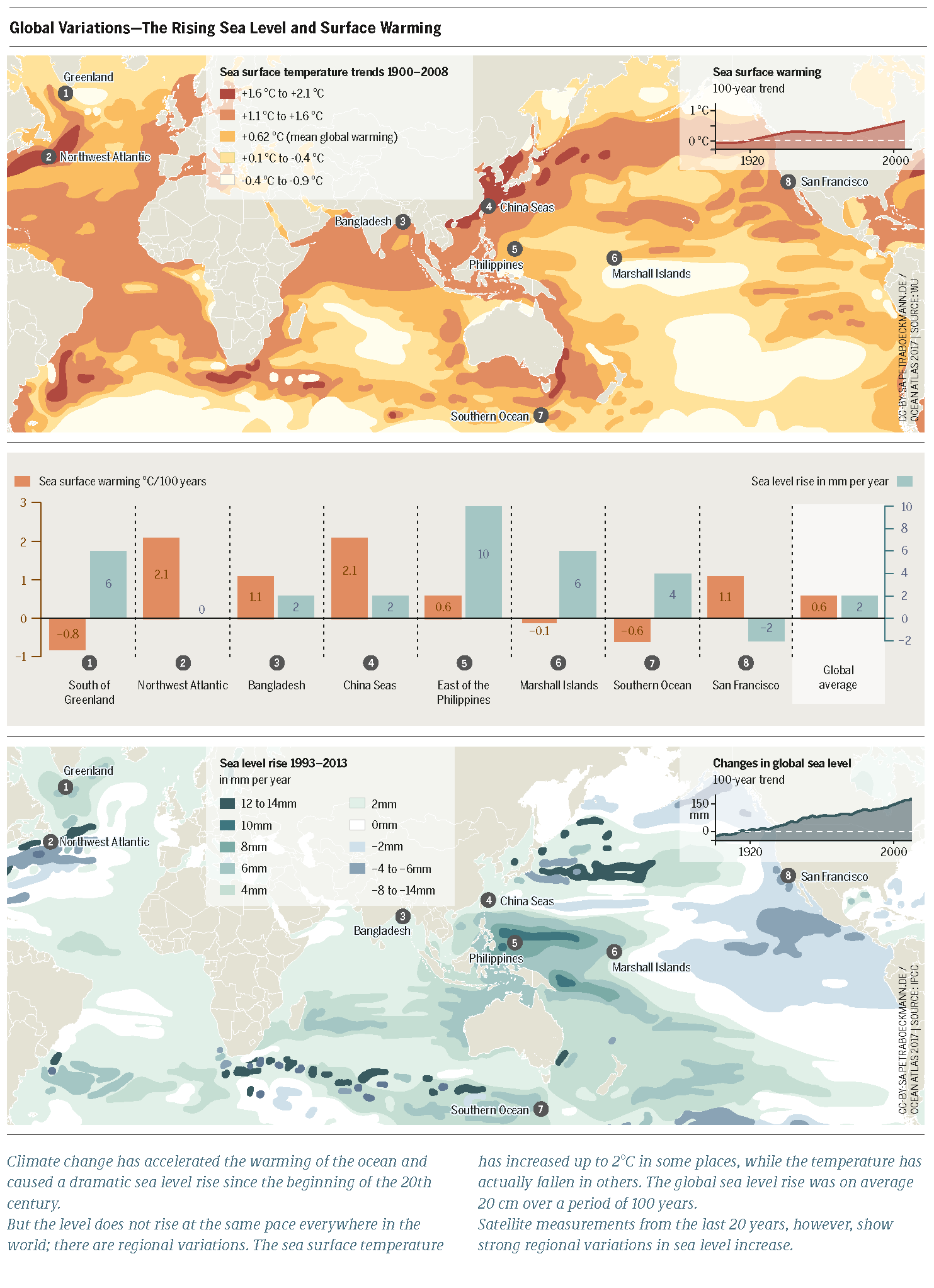

Perhaps one of the most major issues associated with climate change and increasing global temperatures is that of sea-level rise. It is an issue that many don’t necessarily connect with climate change but the danger of it is very real. There is plenty of evidence that proves sea levels are on the rise and the main reasoning behind this is melting glaciers and ice sheets resulting in both the thermal expansion and rising of seawater due to increasing global temperatures.

We are already seeing the negative effects of sea-level rise, so much so that whole islands such as Tuvalu in the Pacific Ocean may disappear altogether within the next century. In 2014, the Tuvalu Prime Minister, Enele Sopoaga said that sea-level rise was ‘like a weapon of mass destruction,’ and it is clear to see why. The small island of Tuvalu only has a population of just over 10,500 people, yet over 3,000 Tuvaluans are living in New Zealand, many of whom have left due to the likelihood of their homes disappearing in the coming years.

The problem, however, does not just exist for remote Pacific islands, but rather for an estimated 40% of the entire population of the United States who live in relatively high-population-density coastal areas, as well many other coastal cities around the world. According to Rebecca Lindsey of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), global sea levels continue to rise by 3.4mm each year and this means that ‘roads, bridges, subways, water supplies, oil and gas wells, power plants, sewage treatment plants, landfills… are all at risk’.

As the global population continues to rise, the rate of rural-urban migration is also increasing which is forcing people to live closer to oceans and indeed build on flood plains which are of course prone to flooding. Recent hurricanes Harvey, Maria and Irma have shown the damage that can be done to such houses and urban communities, yet people continue to build and live closer to oceans. With climate change, the likelihood of such storms and extreme weather events is increasing and thus the potential for future damage is not going to decrease.

As for the UK, the main areas at risk include the South West and North East coastlines, but to understand the seriousness of the issue at hand, it is worth focusing on the Holderness coastline of Yorkshire in particular. The coastline is the fastest eroding coastline in all of Europe, retreating 1.5m every year according to a report by Eurosion in 2007. Dozens of homes have disappeared over the past decade and entire towns are at risk despite local initiatives to reduce the impacts of coastal erosion. But what does coastal erosion leading to the destruction of houses have to do with climate change?

Well, it is quite simple actually. Climate change leads to rising sea levels, as already discussed, and this will therefore result in increased rates of coastal erosion. According to the British Geological Survey, ‘when these two factors are combined it will have the effect of focusing wave energy closer to the shore and cliff faces, leading to increased rates of coastal erosion in areas where cliffs are composed of soft rocks’. It is also worth noting that climate change also leads to more extreme weather events such as storms and heavy rainfall in this part of the world, and this amalgamation of factors will worsen rates of erosion resulting in more homes being at risk of destruction. More than 312,000 people live on this coastline and whilst not all of them live in such proximity to the sea, many choose to, but this choice may no longer be a luxury in the coming years.

So the question remains: How do we respond to such a threat? Well, potential responses are of course varied, they will inevitably be very costly and will require even more international co-operation which has proven difficult in the past due to competing interests of nation-states. One way of adapting to the threats faced is by strengthening sea defences and building homes further inland but this fails to tackle the problem, rather it only reacts to it. In a 2000 report, the Center for Climate and Energy Solutions concluded that ‘major coastal cities such as New Orleans, Miami, New York, and Washington, DC, will have to upgrade flood defences and drainage systems or risk-averse consequences’. These strategies therefore should be used in conjunction with mitigation strategies that aim at decreasing the rate of global warming.

Building homes away from oceans, therefore, is a good strategy to reduce the likelihood of them being affected by rising sea levels, however, it is also imperative that these homes are more energy-efficient than current ones. A real impetus is thus required by governments to persuade people to purchase homes that promote energy efficiency, and this could entail the use of solar panels, triple-glazed windows or much better insulation in the roof area in particular. More efficient homes would reduce the average person’s carbon footprint, thus adding to existing international efforts to combat climate change, but it is only a small step in the right direction, but definitely, one that is a leap forward for mankind.