Should I rent or buy a property? This is a question I have come across various times on social media.

My initial feeling is that buying a property is a pursuit that has been pushed heavily over the years by those who bought their homes for considerably less and have thereby been able to enjoy its long-term benefits. Notably, this is the Baby Boomer generation. Secondly, the majority of retail banks’ business is in the mortgage market, where interest is gleaned through mortgage provision. You only need to look back to the most recent financial crisis to see how far-reaching the mortgage business can be.

I recently wrote an article on London house pricing and why these are increasing so substantially. In summary, it explores how the combination of banks allowing less leverage and requiring a greater initial deposit has increased the rate of renting, while low-interest-rate policy, quantitative easing and low housing stock has caused prices to rise. This has caused people to rent, yet it seems their actual goal is to own a home. Why?

This article was taken from here.

“Dear Emily,

“I’m 30 years old, and my husband and I are thinking about buying a house. He’s all for it, but frankly, I’m terrified of the idea of taking on a mortgage. I know several people who lost their homes during the financial crisis. The housing market seems like it isn’t the sure thing everyone said it was. And we have significant student loan debt as it is. So my question is—is homeownership really all it’s cracked up to be? And what should young people do when they’re already swimming in debt as is?“

“Dear Renter,

I distinctly remember the time in 2006 when a relative told me I should “definitely” buy a house because “the housing market always goes up.” This was obviously not good advice, though it certainly reflects prevailing wisdom at the time. And I can see why in the wake of the housing crisis, you’d fear that the housing market always goes down. Which is also not true.

There is one unambiguous argument in favor of buying a house: Sometimes it is hard to rent the house you want. In most places, if you want to live in a single-family detached house, there are not many rental options, certainly not long-term ones. So you may find yourself coming up short on good rentals, and buying may be the only way to get what you want.

However, let’s assume that you are happily renting someplace and your only motivation to buy is financial. Is it cheaper to rent or buy? In equilibrium, the answer is: The price to rent or buy should be about the same. Why is that?

Imagine that rents were so high that you could buy a place and rent it out and still have loads of money left over—even after paying the mortgage, maintenance, and everything else. If that happens, the market will adjust. People will start coming in, buying properties, and renting them out. But as apartment-hunters have more options to choose from, rental prices will fall. And they’ll fall to the point where the rental price just about covers the cost of owning.

Alternatively, if rents were so low that owners would lose money renting houses, they’d stop doing it. But as the number of available rentals goes down, the prices will go up. And they’ll go up to the point where the rental price will cover the cost of owning.

This is an example of what economists call “equilibrium” and it means that ultimately, it will likely cost you about the same to rent or to buy.

“You can also try to do this calculation directly. Think about what it costs you to rent. Then think about what it would cost to buy the same quality house. Take into account the mortgage, of course, but also insurance, maintenance, foregone interest on the down payment, and the value of your time spent fixing things that the landlord would fix in a rental. I suspect you’ll find that the costs are about the same.

Given this reality, the only other reasoning for buying a house is the view that the “housing market always goes up,” so when you sell, you’ll make money. But in retrospect of the property market crash, this isn’t necessarily the case. Equally, the housing market also doesn’t always go down, so this isn’t such a strong argument, either.

As to your debt question, student debt may limit your ability to get a mortgage, but shouldn’t keep you from buying a house if you want to. Your housing debt is collateralized by your house, so unless the value of your house goes down so much that you’re underwater on your mortgage, it’s not considered debt in the same sense that your student debt is.

Finally, the time horizon matters. There are a lot of fixed costs with buying a house: pay the realtor, closing costs, etc. If you are going to own a house for 30 years, these do not matter so much overall. But if you’re planning to sell in a few years, they significantly raise the effective buying price. And if you rent, so much the easier to flee the coming war with Australia.“

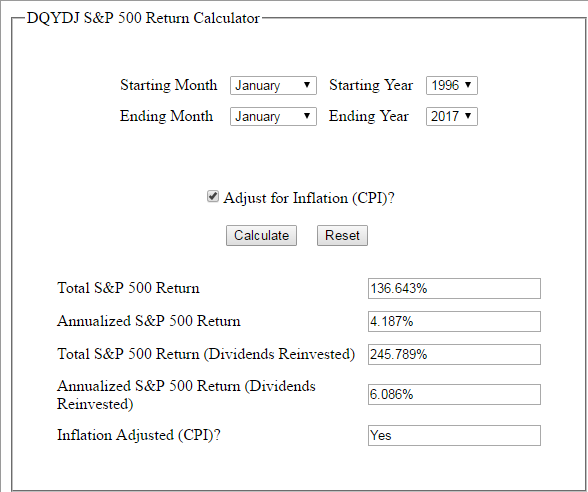

There are various reasons why someone may want to buy a home as discussed above. I consider that the initial outlay of a down payment could be better invested elsewhere. Note that any 20 year period of investing (and reinvesting dividends) in the SP500 has led only to a profit. See here:

If the rationale for buying is simply that you want to install your funds in assets, then I would suggest some more sustainable alternatives with stronger reasoning. If you add in the costs associated with being a mortgage borrower (interest payments, maintenance, insurance, renovation etc), consider if you would be able to achieve a 246% return in a 20 year period -this is one huge opportunity cost, as well as very illiquid.

I understand the above is a great hindsight analysis, but the facts suggest that no one has ever lost money over a 20 year period while investing in the SP500 (as long as we are calculating purely from the principal investment, and with dividends reinvested). Meanwhile, many people have suffered a financial loss on homeownership due to it being an illiquid asset.

Of course, you can release equity in your home to finance other investments, however, this is not necessarily a given investment strategy for the future due to no knowledge of future housing price appreciation or viability for remortgaging. This brings me to my next point.

Buying may be seen as more attractive, but must be considered alongside the percentage of your income taken up by your mortgage. For example, rent may be £1500 and a mortgage £1300, but would your emergency fund be able to cover mortgage payments, if, say, you found yourself unemployed? Or, what if you’re utilising 60% of your income in paying a mortgage plus homeownership costs? Renting provides a certain flexibility in an economic climate where the future is very uncertain. If you were to lose your job, you could quickly move somewhere with lower costs, and avoid a very big mess.

All in all, these factors are subject to personal circumstances that come into play. Nonetheless, it is essential to bear in mind opportunity costs and long-term costs that may not be associated with renting.

‘I refuse to pay someone else’s mortgage’

This is something I often hear. It might be worth noting that costs such as these almost equate to the level of interest payments you would normally pay your bank.

As translated from the French term ‘death pledge’, with my satire directed entirely at the contract’s longevity, a mortgage as we know it is classed as a liability until it’s paid off, thereby meaning a house cannot be considered an asset until that obligation is fulfilled. In addition, considering buying a home solely as an investment is arguably a poor incentive, since house prices have barely outpaced inflation over the last 60 years. However, this does not make it a poor purchase.

The following video link offers a summary of what I have said:

Note, the mortgage calculation equation is wrong. It should be E = P×r×(1 + r)n/((1 + r)n – 1), where E = monthly payment owed to the bank, P$ = loan amount, r = interest rate of loan, n = amount of months loan is for.