For the last 10 years, London has been experiencing a massive rise in house prices. It’s practically impossible for a first-time buyer to get on the ladder – banks don’t want to lend with as much leverage (the money borrowed relative to salary, credit rating and initial down payment) and this is seriously pricing out buyers young and old.

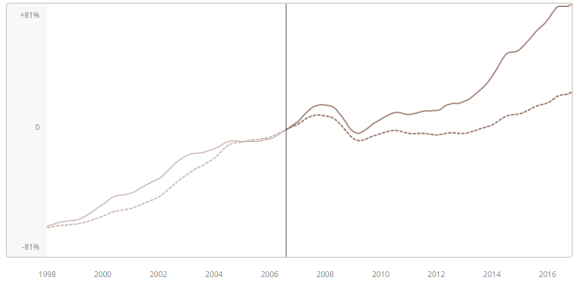

The issue is certainly countrywide, however, London buyers face the biggest hit as seen by the following chart.

The dashed line is the UK housing price index; the filled line is London’s housing price index. There is roughly a 75% difference between the two measures (at current levels).

But why has this happened? If we note the above chart we see that the recent acceleration began from about 2009/10. During this period, the Bank of England had decreased interest rates to their lowest level ever and had introduced something known as Quantitative Easing. I won’t go too deep into the intricacies of it*, but they end up increasing the amount of money in circulation to boost consumer spending and increase inflation to try and normalise the economy after the 2008 crash. If you can’t get a good return on your money by leaving it in a bank account (interest rates are too low) then where is the next best place? Property. London is the draw for these people with cash holdings in the UK.

*For those who may understand this part: during QE, the central bank purchases bonds from institutions (banks, pension funds, hedge funds) to stimulate the economy. This suppressed bond yields and incentivises the desire to seek yield. Therefore, we have stock markets hitting all-time highs and cheap financing of housing which pushes prices up.

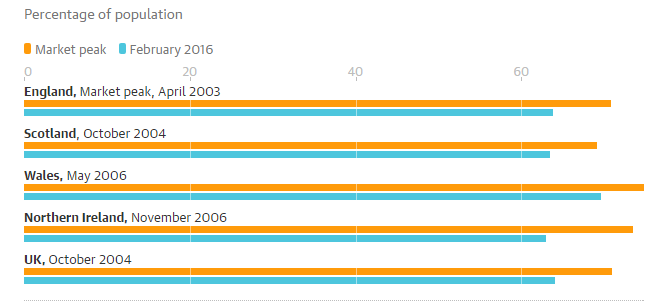

So what happens when you can’t afford to buy? You’re forced to rent. Homeownership last year dropped to its lowest rate in 30 years. In February 2016, it had fallen to 58% in London. London’s peak ownership during the housing boom of the early 2000s was 64% and England’s was 71%. Peak ownership and the new ownership as of Feb last year is shown by the following chart.

I don’t want to get too political/ideological here, but what this shows is a transfer of wealth to the ‘haves’ (landlords, pension funds who own property etc) from the have nots (first-time buyers, young people). Additionally, remember Margaret Thatcher’s ‘Right to Buy’ scheme? People were able to buy their council houses at a massive discount – 20 years later they’re worth 4/5 times more. This disturbance of the supply/demand dynamic has not helped with the velocity of long term price increases.

Additionally, foreign investors have caused a massive rise in London house prices especially. Above I mentioned investors using the property as cash holdings, but why else? Well, the appreciation of London property far outweighs the rate of inflation in a relatively short time horizon. This means that the cash they have used on the property appreciates by the difference between inflation and annual appreciation, minus any costs from taxes/solicitors etc. For them, it’s merely a bank account which is going to give a better rate of return than a traditional account, be less risky than investing in stocks or shares and much of the time, and they can get around capital controls in their countries (see Russia, China etc).

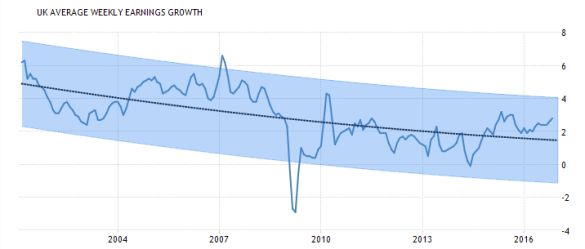

What this also shows is another massive longer-term issue which is low wage growth. Relative to our (I was born in 1992 so pretty much anyone from 1988-1999) parents, we earn 20% less on average.

You can see that the marginal weekly increases in wages over the last 16 or so years have been in constant decline. We have not been above 4% since 2010. This is where a slight bitterness comes in since it is the baby boomers (those born just after the war) and our parents who have kind of gotten us into this situation (more so the baby boomers though)! Now if we combine that with rising house prices, do we really stand a chance of getting onto the ladder.

What can be done about this problem?

Many say that building more houses will fix the issue. This is merely my opinion, but this is not a long term solution. What needs to be done is for global central banks to re-assess their strategies of programmes such as Quantitative Easing and increase their respective base rates. By increasing the base rate, you are simply increasing the cost of investment by restricting the supply of credit. You may say this is a very bad idea since growth is still quite low, but I think that has been equally as bad as the no interest rate policy that has been followed post-2008, where the majority of people have not been able to save while cheap money has been given to the ‘haves’.

Alternatively, we could introduce a land value tax. This is the main overriding feature of something called Georgism.

This is an economic system whereby all taxes are abolished for one single tax on land. The reasoning behind this is that no one created land. No one created natural resources. Land should be everyone’s within a state and therefore we should have the ability to argue for optimum use of this land.

I am a right-leaning centrist but this is not a left nor a right issue. The reason being is that we would have no corporate tax, VAT or tax on income. In my view, that is free marketeering in an as best and most efficient way that we can reach, since other taxes impose large inefficiencies on the payer.

In simple terms, imposing a tax on land focuses all members of a society towards conducting individually productive activities. Being a rentier (landlord) is not a productive activity, since there is a lot of deadweight loss.

Just to let you know, half of the value of the U.K. is made up of land, at roughly £5 trillion. No real value is made and there is huge deadweight loss in interest payments, maintenance and exogenous factors that may even make your house not a good investment in the end.

Here’s a quote from Daniel Ricardo, a famous economist and social scientist from a few centuries ago:

A tax on rent would affect rent only; it would fall wholly on landlords, and could not be shifted to any class of consumers. The landlord could not raise his rent, because he would leave unaltered the difference between the produce obtained from the least productive land in cultivation, and that obtained from land of every quality.

—David Ricardo, On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation

This essentially means that the landlord cannot offset an increase in rent to balance his costs. That’s a win-win for those who wish to rent, and one of the ways in which house prices will be lowered in general.

We must remember that this housing issue is not just a UK problem. Scandinavian cities, Vancouver, Toronto, San Francisco, New York, Hong Kong, Singapore, Tokyo are all experiencing the same problems. When you see such a correlation, you have to begin to wonder as to what is causing it, and since most central banks in the developed world have been following the same monetary policy process, or are highly interdependent’s economy, some bells have to start ringing.